HueArts NYS Brown Paper

Findings

Physical space & built environment

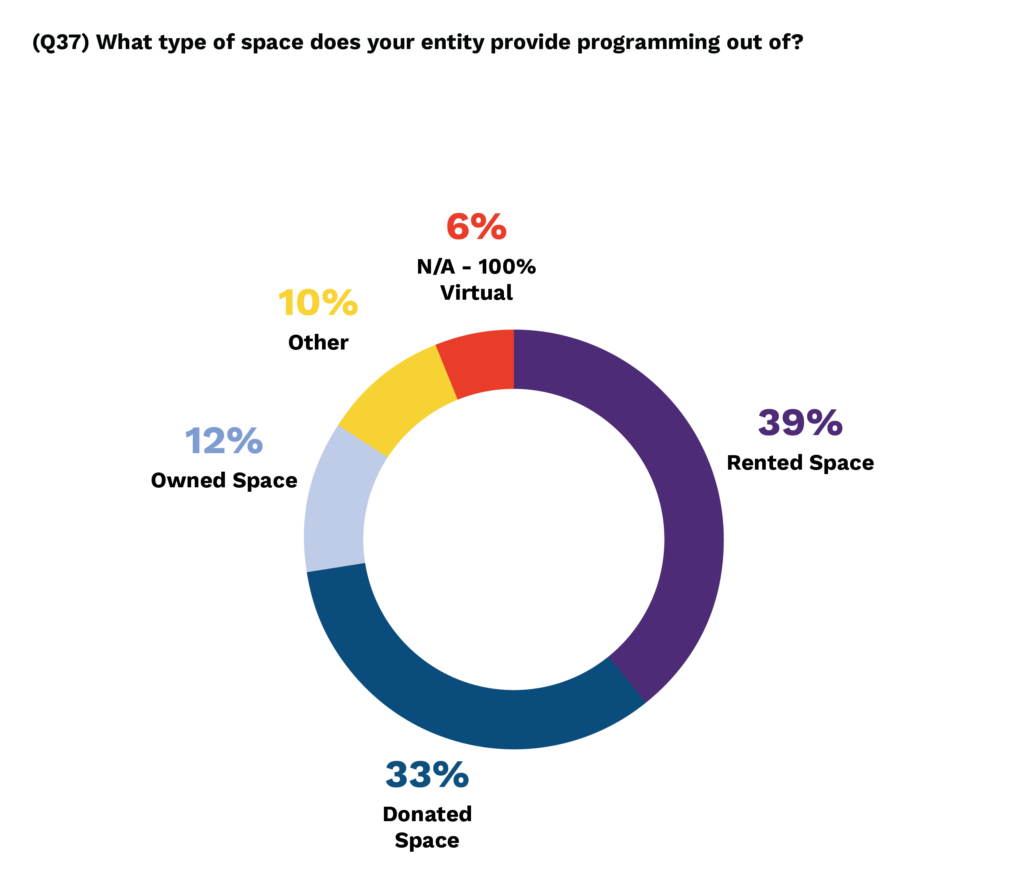

Many Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color arts leaders we spoke with dream of having a dedicated space for their arts entities. Having space allows them to have greater agency over when and how they hold programming, and to establish a footprint within their communities, especially as many are being displaced by gentrification.

At the moment, finding a permanent space is difficult for many arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, and all People of Color. Many rent spaces, but for a significant number of them, the financial burden to even rent a full-time space is beyond what their budgets can bear, especially as gentrification continues to raise prices in their neighborhoods. Many utilize donated spaces or collaborate with one another or with larger institutions to provide programming out of shared spaces.

This constant hunt for space brings instability and additional challenges and expenses. For example, an entity may be required to provide programming during off-hours if they utilize commercial spaces, or they’re required to acquire permits (which sometimes come with a fee) to use public spaces. In other instances, entities are limited by available spaces, and must scale back their programming to fit the venues they can find.

In the face of these challenges, many art entities are interested in pursuing capital campaigns to acquire permanent spaces or are interested in learning more about what it would take to develop a space.

But capital funding is difficult to come by, and metrics for such funding are even more likely to measure success and capability by budget size. This can be frustrating for organizations operating on a small budget which have nevertheless provided consistent programming for many years, or even decades.

Some entities successfully obtained spaces, either with financial support from crowdfunding campaigns or by lobbying for inter-municipal agreements. Though ownership is a seemingly easy solution to champion, it, too, has significant challenges. Maintaining a building is a daunting financial burden, and there is little funding available to support the upkeep of art spaces, often forcing arts leaders to turn to their families and communities for resources. This barrier can be a heavy burden in cases where the communities themselves have scarce financial resources, and face a history of systemic exclusion from property ownership with practices such as redlining (mortgage refusal based on a perception that a neighborhood is a high financial risk), predatory mortgage lending, and appraisal biases.

Gentrification, especially following COVID-19, has been a stymying force across Long Island and upstate New York, triggering land grabs in communities of color and limiting access to space. In many cases, properties are owned by people who live outside the community and are not supportive of the local economy. It is also challenging to navigate the predominantly white developer space, where they may not have any context for, interest in, or understanding of Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all Communities of Color.