HueArts NYS Brown Paper

Findings

Staffing & professional development

Staff Infrastructure

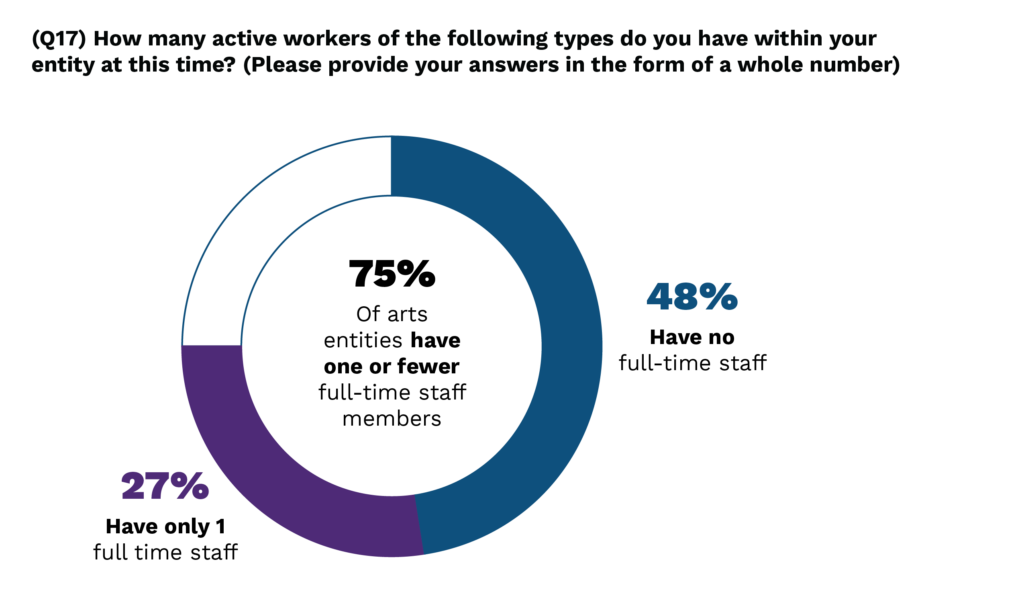

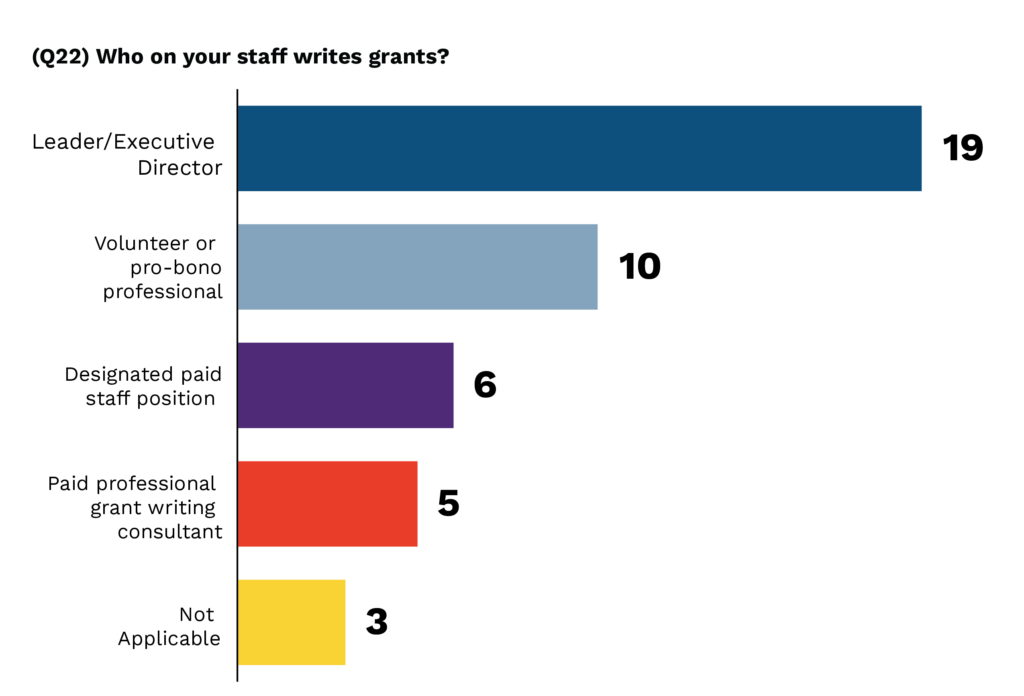

Many Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, and all People of Color arts leaders are juggling multiple roles from developing and implementing programming, to seeking funding, to managing staff and volunteers and planning for organizational sustainability. And to do so on a shoestring budget. Few of the surveyed entities have full-time staff other than their founder and leader, and nearly half have no full time staff at all or operate solely with volunteers. Burnout was a frequent topic of conversation – it is difficult to find balance when these one-person shops, mostly with budgets of less than $50,000, have to compete with fully-staffed entities for grant funding.

Across the board, most, if not all of the arts leaders we talked to needed more staff. Many of these entities rely almost entirely on volunteer labor and are struggling to keep their missions alive and grow their programming with inadequate staff support. What little staff these arts entities do have – typically only the leader (an Executive Director or CEO, often the founder) with the occasional contractor or part time staff – spend much of their time on administrative tasks and fundraising to keep the organization afloat. Only about one third (35%) of those who do have full time staff are able to pay a living wage, and even fewer (24%) are able to provide health care benefits. This is primarily due to a lack of funding for general operating support.

“Borinquen Dance Theater (BDT) is planning to expand classes as a viable cultural Latine organization of 41 years in Rochester. We need our autonomy to sustain BDT for the next 41 plus years. We want to grow the reach of our performances beyond Hispanic Heritage month celebrations and will access existing resources to ensure this growth.

—Nydia Padilla Rodriguez, Borinquen Dance Theatre, Inc.

BDT has been fortunate to be able to sustain its operation with community support from various local funding sources, individual donors, and volunteers. BDT’s 41 years of existence requires discipline, commitment, resilience, funding, and belief of acknowledging Latine arts and culture as a viable resource for urban youth. BDT needs a personnel infrastructure that reflects actual cost for a transition to sustain the next 40 plus years.”

Building capacity in a way that’s supportive and fair for staff is a primary concern for the arts leaders who spoke with us. For many, the inability to provide staff with a living wage or healthcare coverage is a major barrier to actually hiring and retaining the necessary staff to maintain programs, conduct outreach, grow operations, or successfully compete for the funding they urgently need and richly deserve.

Career Development and Professional Development

Many Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, and all People of Color arts leaders are greatly concerned with cultivating the next generation of arts leaders, particularly as current leaders prepare for a leadership transition or plans to grow their staff. They would like to have the capacity to make arts more accessible to their communities, particularly in schools.

Arts leaders recommend starting as early as elementary school and continuing this outreach and education with students through college in teaching young people about the arts, and presenting it as a viable career path – which, as noted above, would also necessitate resources that ensure the arts are indeed a viable and sustainable career path for members of these communities.

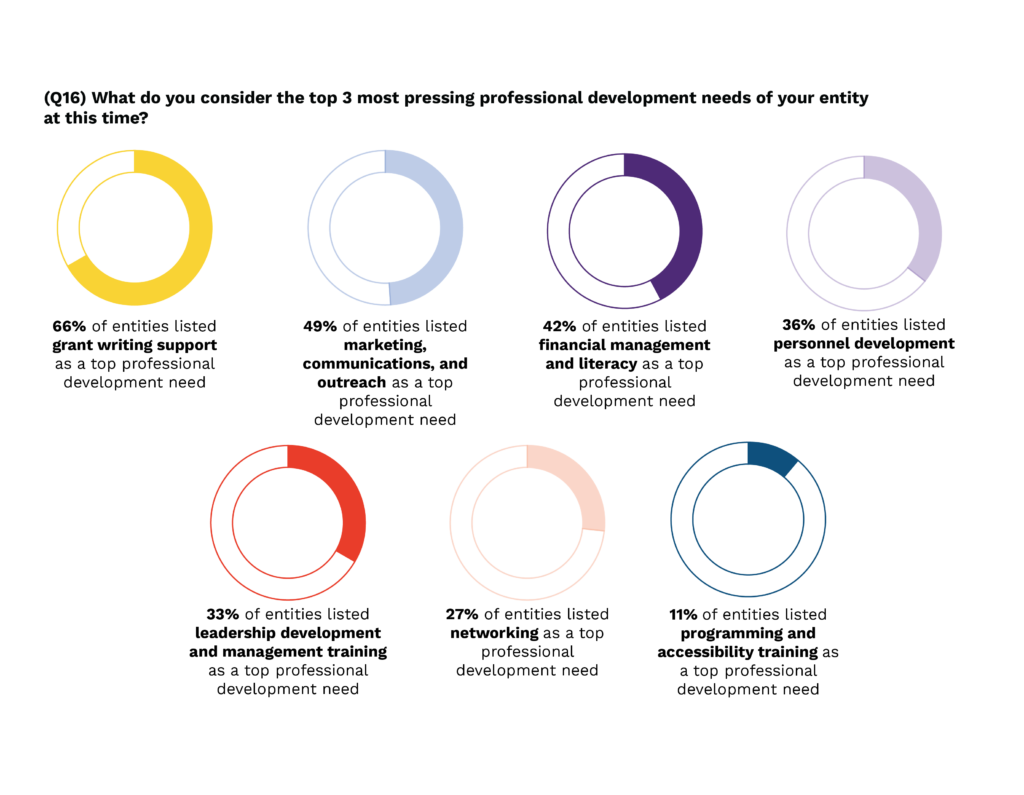

Alongside cultivating future arts and culture leaders is the funding of professional development, including how to start and manage a business, financial literacy in the arts industry, bridging the tech divide, increasing accessibility, networking, conducting outreach and communications, and grant writing. Since many of the arts entities were founded out of necessity by artists, their leaders often never received formal training. Upon identifying the need in their communities, they dove directly into demanding, multifaceted jobs that also left little time or financial resources to seek out and attend such training. One arts leader called for holistic training on nonprofit management and governance specifically for communities of color.

It was noted that training and skills-building to demystify city infrastructure and mechanisms such as permits and codes, is essential as well. These processes can be extremely time-consuming and opaque, but if artists and cultural leaders have limited knowledge of how to navigate them, they may be excluded from opportunities to host festivals, parades, exhibitions, and other programs in public spaces and venues.

Recognizing Value

Surveyed arts leaders stated a keen interest in shifting the narrative around arts and culture within their communities, within funding circles, and within the minds of artists. Overall, they strive to create a society that values the arts, supports artists’ work, and creates sustainable careers within the arts. For many, this is intrinsically connected to bringing people together, and to valuing the cultures and voices of Black, Indigenous, and all People of Color.

“When folks are considering a neighborhood, community, or city, they look at schools, places to visit, and things to do. Art is so undervalued in those conversations and I think of how it would really shift the consciousness around the critical need for art institutions … to build culture and to create space for communities to convene around issues of social justice and what is going on in their community as far as the broader development work …

—Bhawin Suchak, Youth FX

People use the term “food desert” [an area with limited access to affordable nutritious food], but there are [also] arts and cultural deserts, and those are just as damaging to a community and the psyche of a neighborhood.”

In addition to better understanding the value of the arts at large, it is essential for funders, legislators, colleagues, and the general public to understand the value of the particular arts and cultural work produced by arts entities founded, led by, and centering Black, Latine, Indigenous, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color; and to have a greater understanding of the true degree of value they add to communities.

“Our Cultural Center is a resource for Indigenous arts, knowledge, culture bearers, and Indigenous community members. Additionally, the outside world comes to us for speakers, artists, performers, and knowledge holders. This allows our communities to control the type of knowledge out in the world about our people, communities, history, and arts. We have more agency. Funders don’t necessarily recognize that type of service or see it as a service.”

—Dr. Joe Stahlman, Seneca Iroquois National Museum

From preserving and revitalizing cultures and conducting archival research to providing professional development opportunities and educational programming, many arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color see art as a way to meet community needs. Across engagements, many of the arts entities we spoke to described themselves as being one of very few arts spaces in their area centering BIPOC culture and experiences – if not the only one.

A core tenet for many arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color is creating spaces that create, support, and sustain spaces for greater representation of artists who reflect these communities – spaces that do not otherwise exist. Through residency programs and by serving as fiscal sponsors, these arts entities have created ways for artists of color to create work, and be paid, when they are so often excluded by other institutions.

The spaces they create are unfortunately rare, and a goal for many organizations is to create many more such spaces. The goal is to create an environment that allows for joy and “art for art’s sake” without the necessity of being tied to commerce or other external goals. They grow their audience reach of artists, raise awareness and increase the visibility of their communities. In some of the most segregated communities in the state, arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color foster spaces for gathering, connecting, healing, and flourishing.

“When you think of the Hamptons or even New York State, you don’t think about native people still living there. And just that simple idea of representing oneself and trying to persuade people that you are there, has been a challenge.

—Jeremy Dennis, Ma’s House

Many of our (resident) artists have never applied for a residency before or even had an interest; and so I think that having more POC-led organizations would allow more people to prosper and thrive and feel like they belong.”

These entities provide representation of and for their communities where, often, there was none. In taking this approach, they have implicitly added value as they uplift communities which have been marginalized, and amplify dynamic and irreplaceable creative voices within the cultural makeup of the state.

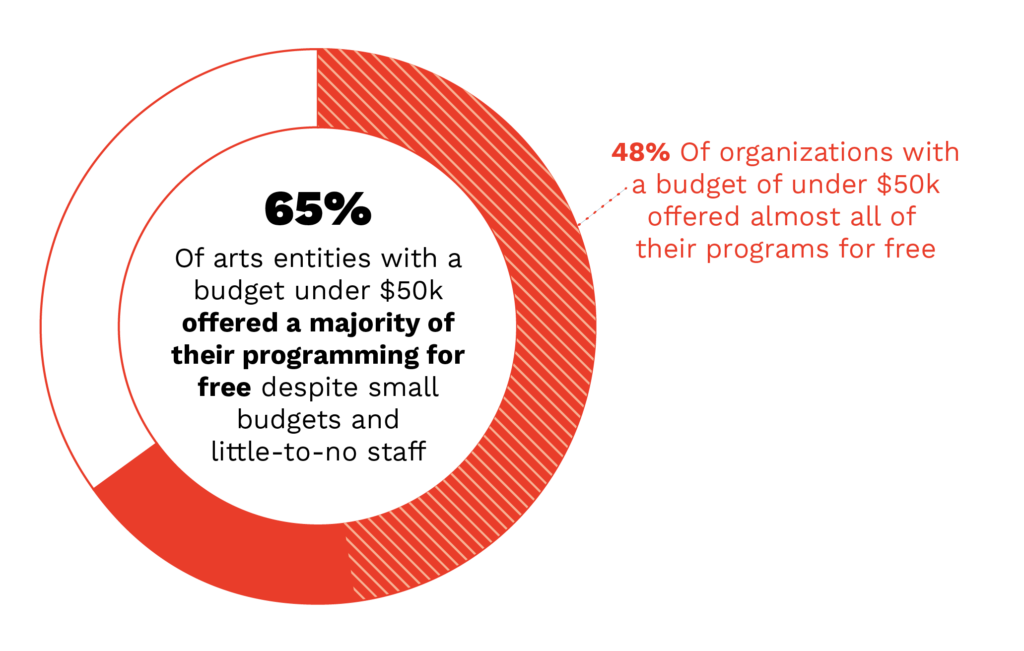

Because of this profoundly held goal around community, accessibility is a key concern for these arts entities. Many take extra care to ensure their programming is available to everyone, including keeping programs affordable (or, in most cases, offering the majority of programs completely free). This may involve seeking additional funding to keep programs free, and at least one organization is working to develop a business model that provides free access specifically to Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color.

Arts and culture entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color across New York State need the time and resources to demonstrate the importance of their work in ways that are understandable to those in power. It takes time and resources to demonstrate this value in a clearly accessible way; and again, traditional metrics often do not take into account this vital work. These arts leaders “demand proper evaluation of the work and labor of POC artists,” and proper payment and resources that reflect that labor and value.

Problematic assumptions which reflect a lack of value recognition can also emerge from arts leaders at predominantly white institutions (PWI) who engage with arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, and all People of Color. At times, colleagues from PWIs can reflect a similar lack of awareness to that of many funders and legislators. They may reach out to meet Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access goals without much understanding or knowledge of the communities, the value of these organizations’ work, or even a complete understanding of a community’s culturally specific arts practice.

“The assumption is that Black people have to be introduced to the arts, despite how our artists and arts have been here and creating work all along.”

—Ineil Quaran, Dope Collective (Buffalo)

Additionally, to meet DEIA goals for grant applications, impact reports, or internal purposes, PWI entities may reach out to arts entities founded, led by, and centering Black, Latine, Indigenous, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color to provide expertise or programming in their spaces. This request benefits the host organization by enabling them to say they’ve worked with communities of color. However, these requests rarely include funding, so that BIPOC labor, expertise, and resources are tapped for free. At least two arts entities also described data being extracted from them without compensation.

Broadly, entities need to be paid for their services – their data, connections, and their experiences. Having time, expertise, or data used without permission or compensation utilizes resources these entities often cannot afford, and also enacts a familiar racist paradigm of presumed ownership and appropriation.

“We are asking people that have mined our art and culture for centuries to appreciate and respect what they have taken for granted. Policymakers, foundations and funders cannot change the way they see us without advocacy and engagement. BIPOC organizations have to become our own advocates and present in a way that these “mainstream” entities understand. It’s not enough that they understand us…we have to prepare to interface with them, they have the money.

—Greer Smith, TRANSART

Right now we are in a moment where organizations and funders acknowledge that without BIPOC representation on their stages and in their final reports, they are not relevant. In many instances local arts councils are trying to do the programming we have been doing without the necessary resources. Politicians will come to our programs for the ‘photo op’ to ensure they have pictures to secure votes from our community and [yet] we have no plan to hold them accountable for an equitable share of the funding. A strategy that moves us forward collectively to engage with funders and audiences would be wonderful.”

Top Photo: Boriquen Dance Theater, Inc.